|

yesterday's news |

|

|

|

Name Tag source We are born fourteen years apart, my only brother and I. On the day my mother receives me in the maternity ward, she looks into my eyes and sees her future with a start: no longer just a woman, now an old woman, she is scrambling to remember the name of the adolescent in front of her (a future version of myself). My mother, the proud owner of genetic practicality, decides then that she’ll give me the same name that my brother holds. One name is easier to remember than two, she reasons. One key of many to her fountain of youth. Besides, what are the chances that when she calls one son, but both come running, she won’t be glad to see the other, too? And if someone should phone for one of us, but get the other on the line, so what? We’re both good boys. |

|

|

Achilles' Neurotransmitter source We spare our loved ones our good moods. Our highs, we’re told, are more intolerable than our lows. There is no antidote to our too-boisterous laughters and our affections, which know no boundaries physical or psychological. When we are puffy with depressions, on the other hand, and swollen with deep hurts and indignations, then we can camouflage ourselves more readily within the routines of the day. Our loved ones tell us of our shortcomings in rasping whispers, when we are sitting on soft flower-upholstered couches or sweeping breadcrumbs from the dinner table after meals. You know that I was once so energetic that I climbed 4000-metres to the top of a mountain? There, I did chin-ups hanging from a previously untouched tree. I fell asleep under the open sky and dreamed about taming wild animals. I ate perch. I ran back home and showered the people closest to me with kind words and breathless optimisms. It’s scenes like this, and others like it, to which our loved ones will refer when searching for the word ‘intolerable.’ |

|

|

Angelhairpulling source They live forty minutes outside of the city, surrounded by grasses that sway and rustle with every gust of wind. They eat heartily and breathe fresh air into their lungs, in a way that calls for sighing with satisfaction. They take hot baths and towel off mightily. They like to rest in their pastures, leaving imprints of their bodies for posterity, or for fifteen minutes, at least. It is egregiously crisp and sunny, one afternoon. The youngest— they are twins — rest in the pastures, side by side. They are schoolchildren; they hold hands and grow red in the face. The older of the youngest (born thirty-six minutes before his sister) announces that his lower back, left side, feels as though a knife is piercing it. Is it appendicitis? Appendicitis! Wrong part of the body. False alarm. The children rise quickly to their feet and scan their surroundings. Indeed, they find that intermittently, in place of blades of grass grow knifes. Dull knives, very dull. There is nothing catastrophic, and nothing violent about the sight of this cultivated flatware. Nevertheless, the children are superstitious, well-versed in a language that does not allow for optimism or linear meaning. A does not mean A. B does not mean B. They wonder aloud what the knives mean, but fail to agree on the metaphor. The discussion ends in tears. They are only children, after all. |

|

|

Rollover and die minutes source Our Uncle Vasya smelled like a man should. He smelled like a men’s catalog: a collection of brisk colognes. Like a men’s catalog that had been left on the sink counter of a men’s bathroom that has two stalls and one urinal and is located in a bar just outside the city off a two-lane road that runs between the forest, between bonfires and summer-homes and laundry wires; the kind of bar where men go to escape their wives and children, and their other wives and children. Which is to say, our Uncle, in addition to smelling like colognes, also smelled like cigarette smoke trapped between threads of rayon and cotton, he smelled like a smoker’s deep cough, he smelled like air freshener, like loose change and hands that had just touched money, like rubber, a dirty floor, like beer and stronger spirits. Our Uncle was a man to be inhaled. -> |

|

|

As it goes, many smells made us nostalgic for our Uncle, after he disappeared. Personally — and I can only speak for myself — I was nostalgic for him even before he disappeared. I felt his absence when he was next to us, when he was next to me, and I couldn’t get enough of his attention, but I knew better than to ask for it. ->

|

One very hot day (Celsius), we sat outside in sleeveless shirts, eating, drinking, and sweating. We swayed under the heat, and under the effects of alcohol then coursing through some of our veins. One of us, swaying and sweating, said that Uncle Vasya had hung himself from a fourth floor balcony, using a damp undershirt and long underwear, just washed. I imagined our Uncle’s body twitching, then growing limp in a thin, blue robe, his slippers sliding from his stiffening toes. Another one of us then said that Uncle Vasya had exposed too many of our nation’s secrets and was interrogated and beaten in custody, and probably killed that way. At that, we sighed romantically and shook our heads. Not one of us had anything of substance to say. Not one of us knew anything about Uncle Vasya save for the fact that he was there one day, and the next day he wasn’t there anymore. Another stereotype, like the rest of us. |

|

Hurricane Václav source He opens his mouth and it’s a natural disaster. Hurricane Gauche flattens the conversation. A sloppy avalanche cascades down his thick tongue, levels whatever semblance of good mood stands in its way. Volunteer search parties and emergency workers scour his environs for survivors. Ha. And that’s what happens, day to day. But on this night of nights, emergency dispatchers are a little busy, thank you. There are stomachs to pump, and cardiopulmonaries to resuscitate. There are limbs, vomit and confetti, cold cuts and broken glass to sweep off of these crowded and historic streets. What a convenience that his speech is stunted, for the moment. A cocktail’s flowing through his veins: part hot hot blood, part fourth flute of champagne, a splash of chemical imbalance. For once, he is a bottle, corked; though nevertheless bubbling within. But he wants to express himself! My God, so like us all! If he can’t set off sparks and fires symbolically, so help him, he will do so literally, through liberal use of low-explosive pyrotechnics! He grabs two sparking sticks in his tight fists. He flails his arms about until the fireworks go off, as do said arms. At present, blood is running down his torso; there is a beautiful display of pops and colors to his left and right. People gawk on over. A woman plants a wet one on his lips. A gentleman: he plants a wet one on his lips. A third party, unfit for categorization: yes, plants a wet one. Meanwhile, the hero of this story concentrates on staying conscious and upright. He’s losing quite a bit of blood. He’s losing balance. The crowd goes wild. The crowd has nothing better to do. The band never showed up, nor was it ever invited. The parade never started; but what parade? They all look at each other. He looks at them. They all look at him. He looks at them. This is not an unpleasant situation. The only thing that bothers him is that, perhaps four hours from now, they will no longer look at him, but he will be two arms the poorer, still. He hates the irreversibility of it. Oh, what a drag. Quick! Before he says something. Somebody get this man a party-blower. |

|

|

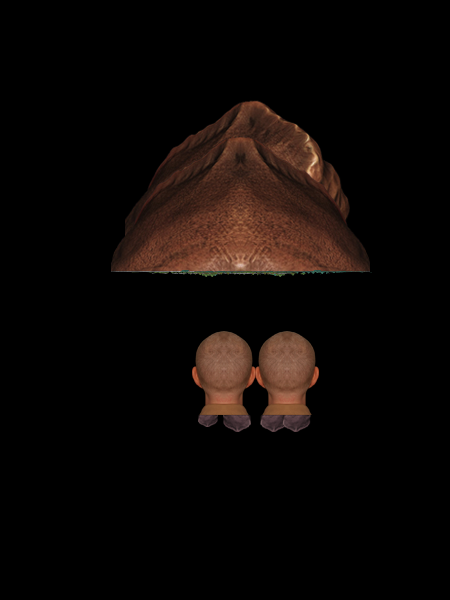

Abel, Abel & Associates source Two men. Two speedos. Early forties. Four long legs and twenty-some protruding ribs. Thick accents, no matter the language. Heads full of hair, chests full of hair, lungs full of Chernobyl (and what lungs aren’t?). They share the rapport of two who’ve seen the same womb and lived to tell about it. Brothers. One lounges on the grey, grey sand. The other does the breast-stroke in the Danube River. He breast strokes his thin neck into one ring of a plastic six-pack yoke. Stretching the plastic from his neck with a finger — the way a man might stretch a very tight, uncomfortable tie — he rushes from the waters, screaming. ‘I’ve just become another victim of society!’ His fellow of the uterus volleys a smack of the lips, a roll of the eyes. ‘Oh, you were born a victim.’ Dry brother hands the dripping one a slice of poppy-seed roulette. 'My Adam’s apple hurts,' says dripping brother. He's trying to swallow, you know, it all. |

|

|

Deity T source He makes the decision to believe in reincarnation. What follows is a shake and a shout: ‘Who are you and what do you want?’ he asks his young cat, with whom he’s shared room and board for two months and counting. This man is a pessimist. He sees the worst in people. Given his new belief in re-embodiment, he now sees the worst in animals and inanimate objects, too. His lamp is an asshole. His chair is a whore. His cat is an adolescent, interested only in that, which makes the teenaged heart race faster. Like antidepressants and topical acne cream. Man swallows a handful of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, out of spite. 'Because I’m boss here.' Cat thinks twice before calling the paramedics. Lick, lick. Scratch, scratch. |

|

|

Forever Twenty One source One perk of being a member of the Undead is that you can eat anything you like without ever gaining a pound or even a kilogram. Because she thinks of herself as a modern woman, however, she doesn’t want to perpetuate stereotypes, so she keeps this information to herself. Here’s what she does not keep to herself: her (figuratively) hot, emaciated bod. Floppy veins be damned. Clammy skin be damned. Decomposing ass? You, too. Damned. Anecdote: She washed up ashore a tourist beach one twilight, scoured her surroundings and found a shirt reading, 'Nobody’s perfect. But I’m pretty close!' She laughed so hard her jaw fell off. She has been wearing the shirt — no pants — ever since. She has also been wearing her jaw (no big deal, it happens all the time). Most assume she’s a drug addict, which she considers a decent enough front, so she goes through the motions and throws in the occasional 'I’m enjoying this release of dopamine!' to avoid suspicion. One morning, she wakes in sunny spirits. It isn’t until she leans over a mirror to snort some stimulants (just for show), that she notices something amiss. In her sleep, someone had plucked the gold teeth from her cold, dead gums. Son of a bitch. Why can’t this world let me be happy? (Her thoughts.) Were it still possible for blood to rush to her face, her cheeks would be red right now. So red, in fact, she’d joke: ‘Call me the People’s Republic of Cheeks.’ |

|

|

Death of a Salmon source Two centenarians sit on a log, which is bobbing in the East Sea. A cruise ship and three thousand passengers sink, leisurely, in the background. The ship’s ‘entertainment captain’ stays buoyant, owing to the inflatable triceps he wears under his sailor’s costume. His makeup is running, so he feels unprofessional and down in spirit. The centenarians, meanwhile, are having a wild, uproarious exchange. Between the two of them, they list upward forty things they find boring, including ‘newborns’ and ‘the bond between mother and child.’ Food from the noontime buffet floats past, and one of the centenarians grabs a puff pastry shell stuffed with salmon. With a gesture: ‘This! This is the brick life is built of!’ Four hours later, the sun will set. Two hours before that, creatures of the sea will detect baked salmon (and human) nearby. Forty-five minutes prior to that, a centenarian artery will clog. No, not the artery stuffed with buttery flakes. The 'entertainment captain' will administer CPR successfully, but the mood will turn dour regardless. |

|

|

Stuffed Papa source

|

|

|

The Attention Famine source

|

|

| © 2011 |